September / October 2025: Taking the play to Hiroshima…

Chapter 1: I Bought These Cream-Puffs from the Neighbourhood Bakery

Ohaiyo gozaimas! Monday morning, September 8th. My alarm goes off at 4.55 a.m. This was the first night in quite a while that I didn’t drop straight off to sleep. I lay awake, trying to relax, counting sheep, doing deep breathing exercises, you name it, but to no avail. Well, this was the eve of a long-planned trip to Japan with my play about Hiroshima, ‘The Mistake’. Who could be calm with that prospect ahead?

I’ve been trying to learn some basic Japanese for the last six weeks – not easy – but it’s been really useful – and actually a lot of fun. I can now say ‘of course’, ‘good idea’ and ‘if it’s alright with you’, along with many other useful phrases and words. But will I be able to have a conversation in Japanese? – not a cat in hell’s chance. However, I am very much looking forward to using one of the most pointless phrases given to me on the online course I’ve been following – yes, you guessed… ‘I bought these cream puffs at the neighbourhood bakery.’

Of course (mochiron) I’ll have to find said bakery first and then buy those aforementioned cream puffs, before accosting some unsuspecting Japanese person on the street, holding up my bag and saying… ‘Kono Chou-cureemu wa kinjono panyai de kaimashita!’

Anyway, it’s now 6.25 a.m. as I lug the same three large, portentous suitcases that journeyed to Chicago and back in April – down the two flights of stairs from my flat to await the cab I’ve booked. With ‘9000 Cars’. I’m relieved to say that despite it being a Monday morning and there being tube strikes taking place, there aren’t yet too many cars on the roads – certainly not 9,000.

Nor is Terminal 3 at Heathrow particularly busy – and as we are allowed two checked cases each on Japan Airlines, (unlike when we travelled to Chicago), there will be no excess to pay as our 5 cases and 1 tatami mat in total are spread between myself, Riko and associate producer Maria – who accompanies us again as she did to the USA.

At the check-in desk I sense my shoulders relax and that magnificent feeling of liberation washes over me as our huge, heavy cases trundle away from us onto the conveyor belt.

At security, even my solid uranium sphere (aka silver boule) makes it through without so much as a twitch from the surveying officers.

There are of course many pleasurable aspects to travelling and to touring, but I remind myself that we are here to take a very serious play to Japan, a play about the first atomic bomb and its devastating consequences, which later in September we will even perform in Hiroshima itself. As I had to keep reminding myself on our US adventure, I am travelling first and foremost as performer and playwright, not as a tourist.

Now, there’s long haul, and there’s extra long haul. To break up our extra long haul I have booked us to go via Helsinki. A chance to stretch my extra long legs – and more! What a lovely airport! Calm, serene, and with a Quiet Space/ Living Room which has bean bags for a nap, comfy chairs, a meditation/prayer space and a room with a soft carpet for stretching and doing yoga on – as recommended by the wall posters. I have the place to myself, and do some yoga which feels so good.

I then go to the loo and there is birdsong playing. I’m definitely coming back here again.

Then it’s onto our long connecting flight and next stop Tokyo. I’ve paid £100 for extra legroom but it’s on the aisle and the service trolleys brushing past me make me a little nervous. It’s a long, tedious flight, with scratchy, broken sleep, but the time passes.

Then we’re through customs, we’re reunited with our vast cases again and are greeted by Jalani, our wonderful young Tokyo associate on this tour, and her husband Toshi – who somehow manages to cram all the cases in the back of his vehicle.

We then drive through the longest road tunnel I’ve ever experienced, (London’s Blackwall Tunnel, eat your heart out) and eventually emerge into the vibrant city of Tokyo. I ask Maria to pinch me. She does. Ouch!!!

But it’s true. We’re actually here. To perform a play which will have such a profound emotional resonance for Japanese audiences. And we’ll perform it in a new bilingual version, with Riko speaking all her 1945 survivor role in Japanese and her role as a modern Japanese woman in search of answers in English.

A huge challenge for her but she’s definitely up to it.

We drop the set, props and costumes off at Studio Actre, a perfect little 70-seat theatre, our venue for 9 performances, and meet Yuri-san who seems to be a young Japanese renaissance man, running the venue, creating and operating the lighting design, doing DIY around the place, and even making sure the restrooms are clean and presentable.

Maria has family in Tokyo but Riko and I each have an apartment booked in a small block. In fact an incredibly small apartment in a very small block.

I’m so glad I decided against bringing a cat. There would be no room to swing it in. And the heat! The humidity! How does the aircon work? It’s not obvious to me – and all the clues are in Japanese, and reading Japanese is a whole other ball game from trying to speak it. But Riko comes to the rescue – and as a result that night I will have the opportunity to sleep in something resembling a fridge.

But first an evening stroll, enjoying the lively streets of Nakano, where we are staying, north-west of the city. I watch a man, doing an incredible balancing act on bricks and circular rubber tubes perched on top of a high rostrum near the station watched by a crowd of fascinated onlookers.

Then after a Japanese supper it’s back to the fridge and as I drift off towards sleep, hoping to conquer my jet lag, I realise I haven’t yet located my neighbourhood bakery! I also think back to the man doing the amazing balancing act. He was no longer in the flush of youth. And I’m reminded of my own demanding balancing act, trying to pull off these two tours to the USA and Japan.

Well, we managed to pull off the US tour… and in the morning, if I haven’t been frozen into an immovable block of ice, we’ll start our Japanese adventure.

Chapter 2: The Real Devil Is War

‘I’m So Grateful…’ ‘We’re So Grateful…’

Those words are ringing in my ears as I walk back to my tiny apartment in the balmy Tokyo evening, after our first ever bilingual performance of The Mistake – indeed, our first ever performance of the play in Japan. ‘This play – so important.’ ‘Very important, this play you have written.’

‘In Japan we feel that only Japanese can understand all the feelings around the atomic bomb. But your play shows that a western person has understood those feelings and understands what the people in Hiroshima suffered.’

This is all incredibly humbling, as you can imagine, but also a real affirmation of what I hoped for in bringing this play to Japan.

Hang on, I’ve skipped a few days.

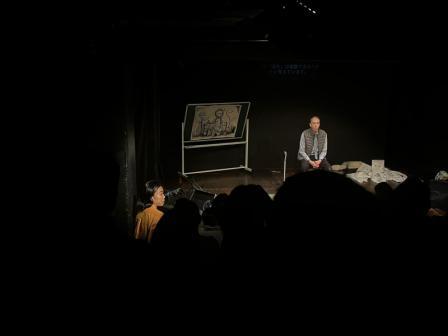

Two days earlier, we meet our young, energetic and oh so enthusiastic team at the theatre, for technical rehearsals. Riko takes charge of marking up the floor with red tape to suggest a squash court – where the chain reaction experiment (a scene in the play) took place in Chicago. She is a perfectionist, takes her time and marks it up beautifully. Then there are the subtitles to sort out, which will be projected on the back wall above the blackboard used in the play.

Oh yes, the blackboard – which we couldn’t transport to the US earlier this year, so had to source boards there, and which we couldn’t transport to Japan either. So a board has been purchased for us here – which however is not very high. The reason being that Japanese people are not generally 6’ 2’’ tall (as I am). So I will have to stoop a little in performance to chalk up my equations (he stoops to conquer?)

Talking of stooping, there isn’t too much space backstage – so I offer Riko the main little dressing room area while I elect to take what might be the smallest dressing room in the world – well, certainly in my career. A cupboard under the stairs, you might describe it as. But it has a curtain and affords me a little privacy. Might need to see an osteopath though, to straighten out my back, once I return to London.

Just before lunch, Riko and I are interviewed by Hisanobu Ito for the AKAHATA newspaper – the daily paper of the Japan Communist Party – a party not as extreme as it sounds, however. In fact, Ito-San interviewed me in London in 2019, not long before I was planning to produce the play for the first time – until a certain world pandemic put paid to those plans. He shows me some recent interviews he has done – and there, staring out of the paper at me, is the face of Jeremy Corbyn – who visited Hiroshima in August. (And who was due to see the play in New York earlier this year and be our guest at a talkback – until he had to cancel, unfortunately.)

At lunch, I jest to Maria that I still haven’t found my local neighbourhood bakery nor those seemingly mythical cream puffs.

We head back to continue work on the play and, during the evening supper break, I go to the cafe next door for some comforting pasta.

When I return, Maria presents me with a beautiful cardboard box.

‘A gift,’ she says.

‘What is it?’

‘Open it and find out.’

I do – and OMG!!!

Chou cureemu!

A magnificent-looking ‘cream puff’!

‘Where?’ I stutter. ‘Where, Maria? Where did you get it?’

‘I’ll show you on the way home.’

I cannot resist it and this seems an appropriate dessert to follow the pasta I had for supper.

And oh boy. It’s not mythical. It’s real.

On the way home at 10pm that evening, Maria shows me the elegant shop on the corner near the station where she bought it from. ‘Temptation Corner’ I christen it…

The next day, Friday, we have our first dress rehearsal – with many a small hitch, with the Japanese dialogue, the timings of the subtitles and various other issues – but nothing major. By the way – did I mention I am speaking Japanese in three short scenes? Just to give myself an extra challenge. As if I don’t have enough to think about. Every day I work on my Japanese lines. I want to sound more than just ‘passable’. But it’s not easy acting in another language! Which makes me marvel afresh at the task Riko has taken on so valiantly, by being involved with this project first in its English and now its bilingual incarnations.

A good night’s sleep follows in my chilly little fridge/apartment and before I know it, it’s Saturday. September 13th. Opening night.

I’m not sure who the lady is on the large poster outside the theatre entrance – or why she seems to have much bigger billing than we do…

Anyway. Fifty people packed into this small venue feels very much like like a full house.

There is much laughter and chatter from the audience as they come in and take their seats. I hear many a ‘konnichiwa’ and ‘konban wa’ in greeting, as I stand in the little wing area offstage right. But the chatter and hubbub soon subsides to be replaced by complete silence. Total attention. No restlessness. No shuffling. No one needing to go to the loo. And thus THE MISTAKE (or ‘AYAMACHI’ in Japanese) takes its course.

At various points throughout the performance I have to get a grip and stop myself being overcome with emotion. Stay focused. Keep telling the story.

Towards the end it’s possible to detect very discreet snuffling, restrained tears, people swallowing their emotion. There’s no standing ovation. Simply applause that doesn’t cease.

I raise a hand and then make a prepared speech – in Japanese and English – using notes as I haven’t yet had time to learn it (but I will by the time we reach Hiroshima.) I make a joke – in Japanese – about my pronunciation, asking for forgiveness. When I end my short speech by saying that I hope we can all continue to work together for a world free of nuclear weapons, I feel myself choking up.

We leave the stage and Riko and I hug and high-five but after a while I realise … they are still applauding.

‘We’d better go back out again,’ I say to Riko.

There is no front of house or bar at Studio Actre so most of the audience just sit and wait for us to come out ten minutes later after we’ve wiped the sweat from our brows and changed.

People stand up and then start queuing patiently to talk to us – to express their gratitude… to share their emotions on witnessing the play. Ito-san, who had interviewed us, is there with his wife, who talks to me at length in Japanese about her responses to the play, her husband trying to keep up with her in translating for me. But I understand what she says when she tells me which line in the play struck her most powerfully…when Shigeko curses the Americans as devils, and her fiancé responds , ‘Hontono akuma wa senso nanndakara.’

(‘The real devil is war.’)

Is this evening one of the most quietly profound experiences of my 40 plus years in the theatre? I’d say, yes.

Our first night audience, predominantly Japanese, has clearly accepted the play with all its different perspectives, its sometimes distressing scenes and its undertow of sadness – accepted it in the spirit in which we have offered it.

Riko in particular is relieved to have received such a moving and positive response from the audience. After all, she’s the one carrying the weight of the survivor’s story in the play.

We’re all pinching ourselves. None of us can quite believe that we’re here, that we’ve done it, that we’ve performed the play in two languages for a Japanese audience in Tokyo. Afterwards we hug and high-five again, Maria joining in too, and all our wonderful young team join in as well, Jalani, Yuri, Zac, Chi, all sharing the joy and relief of an opening night that couldn’t have gone better.

After we tidy up, I walk home in the hot and humid night air, feeling a deep sense of satisfaction, of long months of hard work, my nose to the admin grindstone day after day, finally coming to fruition. I walk past ‘Temptation Corner’, which is now closed, of course.

But I smile to myself and lick my lips. The secret’s out. I’ve located my neighbourhood bakery!

Chapter 3: An American In Tokyo

So, it’s been an eventful few days – but all in a good way. Well, apart from the ‘stuck up a cul-de-sac for half an hour in a huge taxi’ incident. (Did that not make the World Service news?)

On Sunday afternoon we had our second performance of The Mistake for a much quieter and more solemn audience than the previous day.

This was followed by our first Japanese Q and A with the help of an interpreter. Some really interesting and absorbing questions, one person wondering why we hadn’t given Shigeko, the 1945 atomic-bomb survivor, a Hiroshima accent? Good point! In fact, the highly skilled translator of our bilingual script, Yojiro Ichikawa, had asked me initially, ‘Shall I use Hiroshima dialect for Shigeko?’ and I’d said, no – thinking that that might be one extra challenge too many for Riko to take on. But the audience member now went on to say, that having Shigeko played in Japanese without a dialect made her somehow more universal, someone we could all identify with. Interesting.

As in many other Q and A’s, I am asked what gave me the idea for the play – and so I recount my story of reading two interviews in the Guardian newspaper twenty three years ago (the yellowing copy of which I still have and show to the audience), an interview with the pilot and an interview with a survivor – and how I began to wonder whether that might work dramatically…if the descendant of a survivor sought out the pilot in his old age to ask him some tough questions… and thus the seeds of The Mistake were sown.

Sunday evening we were free to relax and next day, Monday 15th, it’s a holiday in Japan, ‘Respect For The Aged Day’. We have an event at the theatre all afternoon – first a Tokyo-based Improvisation group movingly exploring stories of people in Hiroshima just before the bomb was dropped… followed by a short break for the completely full house, while we set up our props, and then it’s The Mistake…followed by another Q and A.

During the play, at almost the halfway point, the blackboard, which has images on both sides and which gets flipped round a number of times, came out of its socket on the left side! Just when Riko has an emotional section of dialogue. Fortunately, I am facing upstage at this point, standing next to the board, and have nothing to say for half a page – which allows me to think quickly. We need to sort the board if we’re going to pull off our coup de theatre later in the play (spoiler alert) when the board magically becomes the wings of the Enola Gay.

My next line is ‘Stop!’ and so I say it twice. Once in character, then once as myself, and I continue – ‘Sumimasen, everybody- we WILL stop – just for a minute – to fix the board. Jalani! Can you help me, please?’ But she’s already there, by my side – and together we put the board back in its socket, tighten the screws and after some applause from the audience, we resume…

Live theatre, eh? There’s nothing like it!

After another excellent Q and A, many people patiently Q – sorry, queue – to offer more thanks and reflections.

Hitomi is a friend of Riko’s and a very well known actor in the theatre in Japan. She has much to say to me – that she was hugely impressed by the performance, that she has played an atomic-bomb survivor herself in a play and so felt deeply empathetic to Shigeko’s plight in The Mistake. She says that the line that really struck her, towards the end, was Leo saying ‘The one thing I could not do was turn back the clock…’ Hitomi says it’s so agonising that we can’t turn back the clock and prevent these appalling events from happening – but nevertheless we can’t give up, we have to keep striving for a world free of these weapons. Her passion is infectious.

Then a married couple speak to me. She sounds German. He is clearly American. They tell me that they were arguing about the bomb at breakfast that morning in anticipation of seeing the play.

He says that his father had been serving in the far East towards the end of the war, ready to invade and quite possibly die, if the atom bomb hadn’t been dropped.

So he had always been brought up to believe that dropping the bomb was crucial to ending the war and preventing even more loss of life.

He then looks at me and says, ‘But my opinions on that have been changed by watching your play today. It’s given me a lot of food for thought.’

I have so valued the reactions of Japanese audiences to the play thus far. But this comment from an American in Tokyo – well, it’s hard to describe how it made me feel. If theatre can open hearts and minds like this then it is truly doing something invaluable – especially in these ever-more fragile and fractious times.

After flopping down in the cafe next door to eat some supper and reflect on the day, I walk back to my miniature apartment, and am nearly RUN OVER by a cyclist on the pavement! – of which there are so many…so many more than in London.

Alas, I haven’t yet learned the Japanese for ‘Hey, it’s Respect for the Aged Day! Show some respect for an old guy, can’t you, on this day of all days! I might look sprightly, but back home I get the state pension, doncha know?’

That would be some sentence to master in Japanese. Perhaps I’ll learn it for a future visit.

This is the first time I’ve felt annoyed on the streets of Tokyo, the first time I’ve almost shouted at someone. I’m glad I didn’t though. I’ve mostly been so taken with the engaging friendliness of the Japanese people I’ve met thus far.

Anyway, I haul my aged disrespected bod up the four flights of stairs to my shoebox-sized room and flop down onto the bed – which is a decent-sized double. A single bed would have been more than enough and would have meant I could practice dance moves and yoga (and been able to swing a cat) without thumping my head on the door and bashing my feet against the legs of the bed.

The close shave with the cyclist is now a fading memory though, and so, no longer irritated, I drift off towards sleep, in readiness for an early start tomorrow – our first schools performance.

Not in the theatre however. We have to pack up most of our set and order a large cab to transport the suitcases and three of us in the morning rush hour traffic to the British School in Tokyo. Inevitably we have to leave the blackboard behind but hope the school can provide one we can work with.

Despite the traffic we make good time, and the driver draws up alongside the entrance to the campus half an hour early – only to then overshoot it, not being sure that it is the actual entrance. It is! It is! But too late – we are now back in the traffic and the driver does what seems a reasonable thing, he turns first left then first left again, and drives his substantial vehicle with us all crammed into it, down the narrowest side-street I’ve yet seen in Tokyo. He keeps going. Right to the end. Where he can go no further. It’s a cul-de-sac, a dead end, with no possible way of turning round. I feel my stress levels rising… we were nice and early and now… we’ll be lucky to be on time. The driver, who is incredible polite and very apologetic, now has to reverse all the way up the narrowest side-street in town – trying to avoid the elderly gentleman watering his plants, the lady on her cycle trying to squeeze past and numerous other obstacles.

Eventually, half a lifetime later, we’re out – and back into serious gridlocked traffic. A u-turn, more gridlock, then another u-turn and we’re back at the campus entrance. I unlock my jaw, ungrit my teeth, and we all make a dash with our cases to the school building. Oh boy. I could have done without that tour of the backstreets of Tokyo…

Anyway. We’re here. We are greeted and shown where the plugs and sockets are and so we set up. We are shown the blackboard (whiteboard) on offer – but sadly it’s a bit feeble, doesn’t flip, nor does it roll easily on its castors. Not to worry. We’ll create the plane without a blackboard.

We’re in a brand new drama and music studio space, full of keyboards, a grand piano, a drum kit and a row of ukeleles hanging alongside one wall.‘Hey!’ I say to the others, ‘why don’t we just forget the show and form a band!’

With carpet on the floor the acoustic in the room is dry and pretty dead. Not great for the voice. And the air-con is noisy. But the performance to about 70 of the school’s students goes very well.

Some staff are present including the Principal of the school, Ian, who is the reason we’re here. Many years ago he worked at a school in Norfolk alongside my best friend John, and when John knew about my plans for the play in Japan, it was he who suggested I contacted Ian. And so, here we are…

Ian reminds me that thirty years ago – yes, thirty years – I came to perform my first solo show at their school. That was the last time Ian had seen me – and seen me act. Where have the years gone, we wonder?

After the performance we stay in the music room for a swift lunch, then twenty drama students, who all saw the play, return for a workshop led by Maria.

The students have only just met us but they soon warm up and relax and after an exploration of character transitions – moving between two characters as I often do in the play – and after exploring many and various imaginative uses for a walking stick and other props, we then set up two scenarios.

In the play just two of us, Riko and myself, plus Claire Windsor’s atmospheric soundtrack, create moments like the explosion of the bomb or the chain reaction experiment in Chicago in 1942.

But what if we had a cast if twenty? The students choose a persona and an activity they might be involved with on a Monday morning in wartime when the all-clear has just been given – and then react to the sound of the explosion when we play it to them. Some of them freeze, glued to the spot; others start collapsing in slow motion. To we onlookers, it’s already a very effective tableau.

Next, they all become scientists reacting in different ways as the chain reaction experiment progresses – the tension in the room mounting as the experiment becomes increasingly dangerous.

The students have become more and more trusting as the session has gone on, open to suggestion and exploration – and there is a beautiful solemnity about their work as they create these two different tableaux – proving that there is an infinite variety of ways of staging events and scenes…all that is needed is imagination.

Don’t get me wrong – I really like film, I really like television – at its best. But I love theatre – there’s nothing like it as far as I’m concerned. With a few simple props, some powerful words, talented and daring performers and a generous dollop of imagination from both performers and audience, much magic can be created. Rough magic, to be sure, but magic nevertheless.

Chapter 4: An English Tea Party…

‘I think it would have been good if you’d written something in the play about Okinawa and explored that…’. ‘I think it would have improved the play if there had been more history about the Japanese incursions into China…’

These comments from history students at Rugby School in Tokyo, who came to the theatre on Wednesday 17th September to see The Mistake.

Yes, but… had I done the above, the play would be much longer and far less dramatic. The drama students from the school, however, were greatly taken with the staging, the simple props used in numerous ways, the character transitions, the swift switches in time and place – and all the students agreed that just two people telling such a powerful story in this way was, as one student kept reiterating:

‘Admirable. Really admirable.’

We were excited to have performed to two international schools but, as someone from the British Council in Japan said, after watching the play, ‘This really ought to be seen in Japanese schools.’ Yes, we’d love the opportunity to do that, but how?

I need to find someone in Japan who could set up such performances…

We’d now worked seven days non-stop and so all needed a day off.

I start my day off, as I have done most days in the last week, heading to a cafe I’ve discovered where the only noise is the gentle jazz they play – which enabled my first proper conversation in Japanese…

‘Watashi wa, kono jazz wa, suki desu! (I Iike this jazz!) Jazz wa, suki desu ka?’ (Do you like this jazz?)

To which the barista answers, ‘Hai. Suki desu.’

(Yeah, I like it.)

It’s as if I’ve been living in Japan all my life…

Talking of ‘character transitions’, after my cafe latte and cinnamon bun, I transition into a tourist, attempting to navigate the Tokyo Metro for the first time, heading for the impressive Meiji Shrine. I am not alone. Hundreds of other tourists have the same idea.

The Shrine is part of Yogogi Park and I walk under huge, towering trees to get there. I’m actually doing some ‘forest-bathing’, as the Japanese have coined it – and it’s very soothing.

After reaching the shrine, I follow the ritual of throwing in a few coins, bowing twice, clapping my hands twice then bowing once more – while offering up a wish for success for the rest of our Japanese tour, and a wish that our audiences continue to watch with open hearts and minds.

There is a lovely ‘inner garden’ next door, far less crowded, with a water-lily pond and tranquil walkways…I realise I’m feeling pretty wound-up, what with the demands of the tour – the pre-tour prep, the long journey here, then opening the show in Tokyo and the subsequent performances. A gentle stroll in a Japanese garden is just what the doctor ordered.

While in tourist mode, I head to Tokyo Station to book my ‘bullet-train’ tickets for next week when we will head south – and I see a sign saying that in the event of an earthquake, ‘the entire building may sway slowly’! I’m not sure how to react. Anxious that I’m in earthquake-territory, or reassured that if it happens while buying train tickets, the building I’m in will only sway slowly and not collapse.

I go for a stroll in the area close to my digs and there’s a sign informing me that I’m on Broadway – Nakano Broadway this time! Off-Broadway, New York in May, Nakano Broadway, Tokyo in September.

I pass a doughnut shop with a large queue forming outside waiting for it to open – but I don’t know the Japanese for ‘Are the doughnuts that good here?’ – so I walk on and reach a lovely little bakery, where an old man sees me staring in the window, and ushers me in. I say, ‘No, after you,’ (in sign language) – but he insists, and I soon realise he is the owner along with his wife.

So as well as purchasing pastries, I have my second major conversation in Japanese which in translation runs something like this…

The wife: ‘You speak good Japanese!’

Me: ‘Oh, not really. Only a little.’

‘No, it’s very good.’

‘No, not that good. Long way to go yet…’

And that’s when I peter out. I don’t ask whether she has any cream puffs because I can see that she doesn’t.

That evening, in a restaurant where no English is spoken, I just about manage to order something, and then I point to a tempting picture of a glass of pineapple juice. When I take a couple of swigs it nearly blows my head off. ‘Arukoru?’ (Alcohol?)

‘Hai!’ replies the waiter.

Hmm, I’ve not been drinking any alcohol while doing this play, to keep me as razor sharp as possible. But as a result of this mix-up, I at least learn the word for ‘non-alcoholic drink’. Not a difficult word. ‘Sofuto durinko.’

We have four more performances in Tokyo, plus two Q and A sessions, plus our get-out, all in the space of three days. Some people travel considerable distances to see us: my friend Sam and his wife Mukti come from one hundred miles away, Professor Toru Kataoka, who has been avidly supporting us on social media, flies from Hokkaido to see us, and I nearly jump out of my skin when I notice someone in the audience who resembles the American student, Caroline, who I coached via Zoom in Shakespearean acting during the Covid years. In fact, it is her!

‘What are you doing in Tokyo??’

‘I’m studying music now and am in Tokyo for a month taking a series of master classes.’

On this morning of our last Tokyo performance – which happens to be September 21st and the International Day of Peace appropriately enough – a Japanese journalist interviews Riko and myself. She asks me a number of interesting questions about my intentions and motivations, and then asks me when I was born. ‘One hundred years ago next Tuesday, ’ I jest. But she’s serious. So I confess the truth. Sixty eight.

Revealing this fact to a journalist, it hits me afresh like a piece of new information. Am I really that age? And if I am, should I be lugging huge suitcases around the globe before and after giving a non-stop eighty five minute high-octane, sweat-busting performance with just one other actor? Shouldn’t I be taking it a little bit easier? Or at least, shouldn’t I try harder to find the money to pay a stage manager to join us on our travels and lighten my heavy load?

Questions I have no answers for right now.

Anyway, the last Tokyo show is over. We talk to our guests, then start packing up, and Maria, Riko and I lug the set and props suitcases to a nearby transport firm – located on Nakano Broadway as it happens – before heading back to the theatre for an ‘English tea party’ with our special little crew. Sandwiches, cakes and delicacies and English Breakfast tea.

During tea, I make the mistake – yes, the mistake – of opening an email from a Japanese theatre producer – whose English is not great – and who has some complimentary things to say about the play, but also some negative things. So many Japanese people in our audiences have had nothing but positive responses to The Mistake, but of course, it’s this one set of negative comments that will inevitably prey on my mind. I don’t agree with most of the producer’s reservations but he does make some interesting points about the expression of anger in the play and the harbouring of hatred for the enemy.

But I can’t think about that right now – so I close my phone and pour myself another cuppa.

Gifts are exchanged, hugs are had, laughter and tears are shed, and then it’s a fond farewell to Jalani and her team – as we head south the next morning on the bullet-train: the sleek, futuristic (and always on time) Shinkansen, which will spirit us at speeds of 120 miles an hour to our next destination, Tottori, and the Bird Theatre Festival. The stations at which the train will stop are flashed up in English as well as in Japanese and, as I sit back in my very comfortable seat, I realise that if I stayed on this train it would take me directly to Hiroshima.

‘Not yet,’ I say to myself. That extraordinary experience is still a week away.

Chapter 5: A Japanese Boy’s Response to The Mistake …

Before we reach Hiroshima – the city that I feel I’ve lived in for much of the last decade, but a city that I’ve never actually visited – we have two other destinations. In my case, Nara and Tottori.

It was hard to fill every week of this month-long tour with performances, so we now have two spare days before travelling to Tottori City in western Japan where we have been invited to perform at the Bird Theatre Festival. Riko spends the two days visiting her family in Osaka; Maria stays with family in Tokyo, whereas I have been thinking of revisiting Kyoto – which I last saw twenty five years ago on my only previous visit to Japan, with the Young Vic Theatre Company when we were performing Hamlet.

But Maria nudges me towards Nara, the ancient capital of Japan. ‘If you like temples and shrines, you’ll find some beautiful ones there.’ So that’s what I do – head south on the Shinkansen bullet-train to Nara for two days.

‘On your way to the temples, watch out for the deer,’ Riko advises me. ‘They’re everywhere and if you’re not careful they’ll eat your food.’

My hotel is small but provides me with a decent-sized room, large enough to swing that proverbial cat in, and it’s located right next to the vast Nara Park – which indeed is full of roaming deer, of all ages, and all very docile. Mostly. Two deer with serious-looking horns lock them briefly in combat. There are elderly ladies selling ‘deer crackers’ everywhere, and signs saying ‘Do not bring deer crackers into the temple.’

I have a couple of hours before sunset so I head to the Todaji Shrine, passing by statues of scary-looking ‘protectors’ at the entrance; then on into the shrine itself – where I am greeted by the Great Buddha, the largest statue of the Buddha I’ve ever seen.

Made of copper, it’s forty nine feet high and towers over all of us onlookers and worshippers. I don’t see any signs here saying ‘no photography’, so, after bowing my head, with due reverence I take a few photos, then move round the shrine contemplating the Buddha from all angles: the huge head, the large hands – it’s all pretty breathtaking.

Next morning, after a ‘western’ breakfast at the hotel, delivered in the most beautiful Japanese style, I set off past the deer – deer on the pavement, deer in the flower beds, even a deer in the road on a zebra crossing no less. (Why did the deer cross the road? To get to the other side?) Speeding cars slow right down even though the lights are green and it’s their right of way. The deer in Nara are considered sacred – revered as ‘messengers of the gods’ in the Shinto religion.

I walk along a slowly-rising path lined with hundreds of stone lanterns through beautiful ancient woodland, to the next temple I plan to visit – the Kasuga Taisha Shinto shrine, with its vermilion pillars, and where there are two hundred wisteria trees, which must look stunning in the springtime. This is considered one of the most sacred sites in Japan, but today the inner sanctuary is closed because of a ceremony – which looks to me as if it involves the induction of novice monks. It’s still a serenely peaceful place to be in and walk around, with thousands of cicadas chirruping in the trees, and the entrancing song of birds I’ve never heard in the UK, providing a magical soundscape.

After heading back through the forest (where I once more feel ‘bathed’ again) I visit an exquisitely beautiful landscaped garden.

Next, I want to see the 5-storey pagoda – but, drat! It’s being refurbished and is completely covered up. So I make do with visiting a 3-storey one instead.

The nearby Kofukuji Temple is open, and in its Eastern Golden Hall I see some sculptures which really do take my breath away. There are signs saying ‘no photography’ here – so all I have is their leaflet which only has a few not very satisfactory photos in it…

There’s one sculpture in particular – of an elderly man, unwell, a lay preacher and follower of the Buddha, who sits erect, quietly dignified, looking out at me across the span of eight hundred years. Yes, eight hundred. I stand transfixed before him and time seems to stop. The moving detail the sculptor has captured, the realism of this portrayal compared to the other statues and sculptures nearby which are more devotional or symbolic is a potent reminder to me from the distant past to keep honing my own craft – to keep looking for the details, the truthful revelatory details in portraying human life both as an actor and as a writer of plays.

Next day, I have booked a late morning train – or rather 4 trains – to take me to the small city of Tottori to meet up again with Riko and Maria. Which means I have just enough time to visit another temple – a small tranquil gem tucked away in the side streets of old Nara town.

There’s hardly a soul there and I take time to relish the silence and peace. There are placards describing different types of meditation – one being the Full Moon meditation where if you manage to visualise the full moon then possibly, just possibly, hidden treasures may reveal themselves.

I sit in delicious solitude and try it. Of course, the full moon has many other connotations – some linked to lunacy and madness.

And the question floats into my mind, as I try to visualise the full moon – am I crazy, am I not a little bit insane, to have embarked on these two complicated tours abroad this year?

We have sent the prop suitcases ahead with a transport firm, so I only have to lug my own massive personal suitcase out of the taxi and on to the first of my four trains – requiring three changes – to Tottori. All four are on time to the minute which is pretty impressive.

Tottori is a small city but Shikano, where Bird Theatre Festival is located half an hour away, is positively rural. We are met by our translator Haruna, who drives us alongside the ocean and through gorgeous green wooded hills and small mountains to get there.

Bird Theatre has a lovely building with a cafe, outdoor spaces, a very special gift shop, and an excellent 200 seat theatre. Makoto Nakashima, the charismatic and irresistibly charming artistic director, meets us and shows us around.

‘But you are not performing here,’ he informs us. ‘You’re a ten minute walk away in the City Hall…’

Where there is an eighty-seat theatre, the Assembly Theatre, specially kitted out for the Festival, with two large functional rooms at the back to serve as dressing rooms.

The crew working with us are utterly delightful and so keen to be helpful but they don’t speak a word of English. I throw some of my pidgeon-Japanese around, eliciting smiles and laughter, especially when I keep complimenting their work with ‘Subarashi!’ (‘Great! Fab!)

Maria transmits our lighting and sound requests to Haruna who then translates them to the crew. It’s quite a slow process – and Haruna has to search hard for words, as she has no knowledge of theatre technical terms like upstage, downstage, focusing the lights, slow fade, coming in tighter with that sound cue, etc.

She’s exhausted by the end of the day but has done a wonderful job.

‘Subarashi!’

We are very grateful to have her with us. (Riko of course speaks Japanese but she needs to focus on her performance.). We have a very good dress rehearsal and then on Saturday 27th at 4.30 we will have our first of two performances.

On my way to the venue I walk through the little town of Shikano, pinching myself – I am about to perform my own play in western Japan! How did this happen?

And I ask myself, is this the most rural venue ever on our various Mistake tours?

I pop into the restaurant next door to City Hall and fortify myself with delicious soba noodles – while contemplating the fact that today is International Day for the Total Elimination of Nuclear Weapons.

I then head to the venue and while warming up look out at the empty rows of seats – which have no backs. A bit like the old Bush Theatre in London. But it’s not long before fifty or so Japanese theatre-goers take their place.

The applause at the end of the performance continues for some time after we have left the stage. Riko has started changing but I say we should really go back out again.

The applause in response to when I speak in Japanese at the curtain call, expressing my hope that we all continue to work for a world free of nuclear weapons, is very moving. After the show, we hasten to catch a Japanese company performing in the main theatre – and then it’s party time!

The four companies performing this weekend are feasted by the Bird Theatre Company but are also expected to ‘do a turn’.

We were only told about this the day before and with much else for us to think about, I offer to do the turn and let Maria and Riko sit back and watch. I settle on singing ‘Yellow Submarine’ – with silly goggles, makeshift periscope and a banana doubling as a miniature submarine. Everyone knows the chorus and it goes down very well, I’m relieved to say. I also sing my own new lyrics to ‘Give Peace A Chance’.

‘Everybody’s talkin’ ‘bout

Ukraine, Gaza,

Putin, Netanyahu,

Trump bein’ rude

At the United Nations,

Wars in Africa,

Destruction everywhere…

All we are saying is

Give Peace A Chance…’

The whole of the mainly non-English-speaking party-goers join in the chorus as Riko and Maria hand out peace cranes…

It’s been a truly ‘subarashi’ day but I’m now shattered and can’t wait for my bed. In my tiny room. Very like being on an actual submarine.

When I wake in the early hours, I think about John and Yoko, all the efforts they made for peace. But wars still rage.

As for my modest 80 minute play, what hope can I have that it will effect any change, performing to just a few thousand people at most over these various tours?

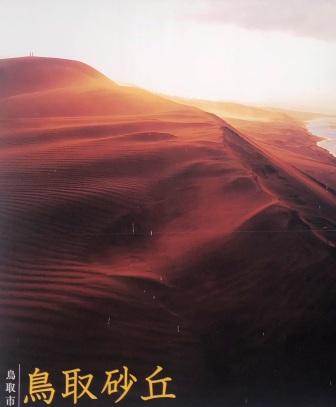

Tottori is famous for its nearby sand dunes, but I have no time to visit – though Riko dashes there in the morning and says they are sensational. I have to make do with taking a picture of a poster. Our second and final show here, to a deeply attentive and completely silent audience, goes extremely well. It’s then time to pack up, say goodbye and bow half a dozen times or more to our glorious young crew and to our translator Haruna.

A twelve year old Japanese boy was in today’s audience – Maria spotted him writing feedback afterwards, leaning on the front of the stage.

His mother ushers him onto the stage when we come back after changing our clothes as he is very keen to express to us how much he had loved the performance. Someone translates. ‘It’s the best theatre show I’ve ever seen.’

He takes a close look at our props, the model plane, the skull, the uranium sphere, takes some photos and then tells us, ‘This play made more of an impact on me than our school visit to the Hiroshima Peace Museum.’

Wow.

When we read his written feedback later, it says, ‘It’s time for the younger generation to take an active role in freeing the world of nuclear weapons.’

Again, wow.

The Oppenheimer film – which didn’t reference the Japanese experience on the ground in Hiroshima at all – reached millions of people, whereas The Mistake can only reach a few thousand at most. But after this boy’s reaction today?

Perhaps this play and our modest small-scale production can have an effect after all. Perhaps that twelve year old Japanese boy will grow up to become a significant campaigner in the struggle to eliminate these terrible weapons once and for all.

Who knows?

Whatever may happen, all I am saying is give peace a chance…

Chapter 6.1: Hiroshima… Meetings with Atomic-Bomb Survivors

Saturday afternoon, October 4th, we take off from Hiroshima Airport to begin the long journey home. What a week it’s been – this final week of our Japanese tour.

In Tottori City on Monday morning, after our two performances at Bird Theatre Festival, we are undecided how to get to Hiroshima with all of our baggage. Six large suitcases, a number of smaller cases, and not forgetting the tatami mat used in the play as well.

There’s a cheap bus all the way to Hiroshima, which is a very tempting option – until we discover that the bus-stop is fifty miles away. The bullet-train beckons, but that would involve a change of trains and then hunting down at least two taxis at Hiroshima Station. So the best option seems to be a minibus and driver – taking us from hotel door to hotel door – but this will cost a cool £500.

I don’t even hesitate. ‘Let’s do it – it will relieve us of so much stress.’ There have been savings in other parts of the budget so I feeI I can justify this expense.

From hotel door to hotel door; from cramped submarine-sized ‘cabin’ to stylish spacious apartment with all mod-cons – located right on Hiroshima’s Peace Boulevard. After five nights cooped up like a budgerigar in my birdcage of a room in Tottori, at last – enough room in which to stretch out, walk about, dance around, open up my suitcases, spread all my clothes and papers about. Room in which to think and reflect.

I feel many emotions coursing through me as the minibus draws ever nearer to the city which has taken up so much of my thinking, my feeling, my creativity, these last few years.

Shortly after arriving, we meet up with Junko, our second wonderful Japanese collaborator for this tour, then head to the home of Toshiko Tanaka. She is the gently inspiring 86-year-old atomic bomb survivor who I met and befriended in London last year – and who at that time invited Riko and myself to her home in Hiroshima should we ever get here.

She’s waiting on the doorstep and when she recognizes me her face cracks open into a huge grin, a heart-melting beaming smile, as she takes my hand and says, ‘This is like a dream – a dream come true!’

I introduce her to Riko, Maria and Junko and we are ushered inside to where family and friends await. There is so much laughter, so much emotion. Riko is deeply moved to have this opportunity of talking with Toshiko and hearing her story first-hand, of surviving the atomic bomb, her subsequent trauma, her turning to art in later years as a way of healing that trauma, and then, only at the age of seventy, at the urging of others, beginning to talk in public about her experiences; travelling, when her health permitted, travelling the world to speak at conferences, schools, all kinds of events – where she would share with her audience the horrors of that August day, in 1945, when she was just six years old, when she lost family and school friends, when she suffered burns and injuries such that at first her mother didn’t recognise her.

At these public events, Toshiko would then take questions and, in conclusion, gently, but so persuasively, so irresistibly, urge everyone listening to ensure that these terrible weapons are never used again.

One of her recommended strategies? To travel and make friends with people in other countries, to reach out to those from different nations, so that should war between those nations ever rear its ugly head, we would resist it, with every fibre of our being, because of the precious friends we have in that country, that nation.

Next, she urges the four of us to go next door where she has a small gallery exhibiting her striking mural art-works, which use ceramics and enamels as well as many other components – all her work referencing in subtle and varied ways different aspects of her experiences of the bomb and her reflections and contemplations of the world, the universe, and how we are all so deeply connected.

There are many exquisite details in these art-works. In one of them I see Einstein’s famous equation – the same equation which is written on the blackboard in my play The Mistake, which Toshiko will attend tomorrow as a guest of honour.

When we return from the gallery she tells us how each of these art-works took her about six months to complete; that while she was working on them she forgot everything else, she could feel her trauma and pain subsiding. We are then greeted by a huge feast of delicacies laid out on the tables – and amidst the devouring of tasty snacks and the clinking of glasses filled with sparkling wine – ‘Kampai!’ we toast – the laughter resumes.

When the subject is serious, Toshiko speaks with earnestness and gravitas, every word carrying profound emotion. But when the subject is not serious she laughs, smiles and is filled with joy. Despite constant bomb-related health issues throughout her life, she has never wanted to come across as a sad old lady bemoaning the past. As a result there have been people – can you believe this? – who have suggested she is not a genuine survivor; because of the joy she so often exudes. (Holocaust-deniers, climate-crisis-deniers…you can now add to the list atomic-bomb-survivor-deniers…)

Ten years ago Toshiko welcomed the grandson of President Truman into her home – the grandson of the man who authorized the dropping of those terrifying atomic bombs. She is a true ambassador for peace and I feel my life has been deeply enriched by meeting her.

The Japanese word for atomic-bomb survivor is ‘hibakusha’ which, strictly translated, means ‘bomb-affected person’. Little do I know that I will soon meet another extraordinary hibakusha.

Next morning, Tuesday September 30th, the day of our performance in the city, I need some time to myself – to visit and contemplate some of the city’s significant sites and memorials.

Sometimes it’s the smaller things that have greater impact. I feel my eyes pricking with tears when I suddenly encounter half a dozen atomic-bomb survivors not far from our aparthotel in Peace Boulevard. But these survivors are trees. Trees that were less than a mile from the epicenter of the atomic blast but somehow survived. Are somehow still alive. 80 years later. What did these trees experience that August day? What unbearable sights did they witness? If trees could talk…

I lay my hands on each of them in turn, then move on – towards one of Hiroshima’s seven rivers – the Motoyasu – and its distinctive T-shaped bridge. This was the target point for the atomic bomb, which I reference more than once in the play. And here it is. I am standing on it. The actual bridge. Rebuilt, restored. Eighty years ago, standing on this spot, I would have been instantly vaporised. I gaze down into the river, I survey its banks, imagining the thousands of wounded and dying taking refuge there, many of them jumping into the water, trying to cool their burns, many dying instantly…

All of which is witnessed in my play.

A short distance away I can see the iconic A-bomb dome – which partially survived the blast and has been carefully preserved as a potent reminder of what happened 80 years ago in this now rebuilt, modern, bustling city.

I walk past an affecting sculpture of a burns-victim… reddish stone, the body slightly abstracted, writhing in agony; on into the Peace Park, where I ring the Peace Bell; where I walk past the flame of peace – which will only be extinguished once the last nuclear weapon has been eliminated from the world; on to visit the children’s memorial – one of many in the city, each one so poignant – this one in tribute to Sadako Sasaki, who folded a thousand paper peace cranes before dying of bomb-related leukemia, aged 12. When she ran out of paper in her hospital bed she would fold tiny cranes from the papers her medicines were wrapped in.

Next, I walk a little further to pay my respects at the Memorial Cenotaph, with its famous inscription – translated into numerous languages. In my play it’s translated as ‘Rest In Peace for the mistake shall not be repeated’. In German, it’s ‘katastrophe’; in French, ‘tragedie’; and in Italian, ‘malvagio’ (evil).

I look up at the blue sky above me and imagine the monstrous swirling black and purple mushroom cloud, towering terrifyingly above the city 80 years ago; I can sense the ghosts of atomic-bomb victims all around – in the air, on the breeze, floating above the river, hovering within the reverberations of the Peace Bell…

And yet the city is now so full of greenery, so full of life, so full of bustle…

In response, however, a simple heartfelt poem materialises in my mind…

The city survives, The earth revives, But one hundred thousand Lost their lives…

Riko and I have been trying not to put too much pressure on ourselves as this day has approached. ‘Let’s just think of it as another performance,’ I say, ‘We’ll do our warm-ups, then give 100% as usual.’ ‘But it’s not as usual,’ Riko says, ‘It’s Hiroshima!’

She’s right. Who am I trying I fool? It most certainly is not just ‘another performance’. I feel my nerves jangling, my stomach churning.

Later that afternoon we set up in the large hall of Hiroshima International House, we assemble the whiteboard we’ve bought online, and before we know it, it’s six o’clock, and 100 people are filing in to take their seats… friends, friends of friends, younger people, older people, Japanese people, English-speaking people, peace activists, strangers who have heard about our visit from a newspaper article, and three atomic-bomb survivors – one of them Toshiko Tanaka, now sitting in the front row accompanied by her English-speaking daughter, Reiko.

We are performing on a stage but it’s quite small, our movements and staging more restricted than we’ve been used to recently – but all goes well, if not perfectly. I have a little trouble with one or two props – due to nerves? – but nothing that the audience would notice. Portraying the pilot of the Enola Gay, Colonel Paul Tibbets, in the very city that he flew over so precisely in order that the first atomic bomb in history could be delivered, is not an easy task for me – it almost feels brutal. But I endeavour to stay true to the character of the man.

The silence and concentration in the room is very moving, and as the play progresses the emotion in the air is audible. Tears. More tears. ‘Stay focused,’ I tell myself. But then, towards the end, as I deliver nuclear physicist Leo Szilard’s penultimate line – ‘The one thing I could not do was turn back the clock’ – I make the simple error of looking straight into the eyes of Toshiko Tanaka, atomic-bomb-survivor, sat there before me in the front row – and I nearly lose it. I so nearly lose it. ‘Get a grip,’ I order myself – which I do, then manage to complete the last few minutes of the play. Riko’s character Shigeko has the final line – spoken in Japanese – but which in English means, ‘I’m sorry if any of this has caused you distress’. That line seems acutely pertinent today of all days, in this city, in front of this audience.

Applause; more applause; then my speech in Japanese thanking them all for being there and fervently hoping that we’ll all continue working for a world free of these monstrous weapons; yet more applause; after which Toshiko is invited onstage to speak about her experiences, while Riko and I quickly change – not before emotionally high-fiving and hugging each other with relief. We then join Toshiko onstage and answer questions and share reflections with the audience.

Some scenes in the play were clearly hard for Toshiko to watch, painful memories flooding back, but she grasps our hands in gratitude, urging us to continue contributing to a more peaceful world through our particular medium of dramatic art.

After we conclude, we mingle with the audience. We meet Keiko Ogura, another atomic-bomb survivor who speaks fluent English and travels the world working for peace. Riko’s mother is also in the audience – she saw the play in New York earlier this year and has come down from Osaka to see her daughter perform in Japanese. She compliments my Japanese speaking in the play (three short scenes) – and Riko then tells me that when her father saw the play in Tokyo two weeks earlier he had declared that my Japanese speaking was better than Johnny Depp’s in the film ‘Minamata’.

Wow. I had no idea. There’s something I’m better at than Johnny Depp.

As people begin to leave, someone tells me there’s another woman who wants to say hello to me. A small 80-year-old woman, whose name is Koko Kondo. I learn that she too is an atomic-bomb survivor. She was a ten-month-old baby at the time, and was pushed out by her mother through a hole in the debris of their home that had collapsed on top of them, with flames getting closer – both of them miraculously surviving and ultimately reuniting with their father, the Methodist minister Reverend Tanimoto, who was in another part of the city.

This is making my head spin.

I have been performing another, shorter, Hiroshima play, called The Priest’s Tale – a solo piece I’ve created from one of the accounts in John Hersey’s seminal book ‘Hiroshima’. In it I play a German Jesuit priest, based in Hiroshima, who survived the blast. This priest, and his fellow Jesuit priests in the city, knew and were friends with the Reverend Tanimoto, who I reference several times in my piece. I even briefly portray Tanimoto.

And now I find myself talking to Reverend Tanimoto’s daughter. Who takes my hand. Who warmly thanks me for the performance of The Mistake she has just seen. Who tells me she will be seeing me again tomorrow. When I am due to perform The Priest’s Tale for English-speaking peace studies students at Hiroshima University. My head spins even more.

I find it hard to process this all.

We say goodbye to Toshiko and her daughter, then it’s time to clear up the hall and wait for a taxi to take us and our cases full of props back to the aparthotel.

What a day. Unforgettable.

Later, in the solitude of my spacious room, I devour the bag of snacks left over from yesterday’s feast, which Toshiko insisted we take home with us – while I reflect on what has just happened this evening: that after so many months and years of preparation, I have performed The Mistake, my play about Hiroshima, alongside a remarkable Japanese performer, Riko Nakazono, in front of atomic-bomb survivors, in the heart of that very city.

Chapter 6.2: Finale.

Wakeful, during my second night in Hiroshima, I recall more poignant details I learned in the last couple of days from Toshiko Tanaka, atomic-bomb survivor. When she gave birth to her first daughter, Reiko, Toshiko’s husband arrived at the hospital looking pale and worried. He counted Reiko’s fingers and toes and when he found that she was born without physical defects he said, ‘Thank you!’ Toshiko realised that, out of love, her husband had never said anything, but had always been secretly concerned about the possible after-effects of the atomic bombing. In my play, Shigeko, suffering from radiation sickness, seriously contemplates whether she should have children, in case they too, like her, will have been ‘contaminated’ by the bomb. The atomic bomb not only wreaked havoc on this two fateful days, August 6th and 9th, but spread its sinister tentacles down the generations.

Eventually, day breaks and I realise it’s October 1st – a new month. We now have only three more days in Japan.

A few years ago, Hiroshima University moved to a campus nestling amidst beautiful tree-clad hills and mountains about an hour’s drive from the city. Their peace studies department were keen to host a performance of The Mistake while we were here, but when they realised a couple of months ago that it would be a bilingual version, they hesitated. They were concerned about the majority of their international non-Japanese speaking students. ‘Could you do it all in English?’ they asked.

Nope. Not possible, I’m afraid.

We’d have performed the bilingual text less than 24 hours earlier and to switch versions – particularly for Riko to switch versions – at such short notice, would be one challenge too many.

Junko, who was organising our Hiroshima performances, then asked me about my solo piece, The Priest’s Tale, in which I enact the story of a European atomic-bomb survivor. Could I perhaps do that instead? It took me no longer than the blink of an eye to decide – yes! – I’d be thrilled to perform this other Hiroshima-related piece for the students.

It would mean having to pack my priest’s ‘dog-collar’, and a few other bits of costume as well as two or three extra props, in addition to everything else I was packing to bring to Japan. But my suitcases being so cavernous, somehow I’d cram everything in.

Would I be able to cram both plays into my less than cavernous brain, though?

Well, I’d performed The Priest’s Tale twice in early August, so it was still fairly fresh in my mind. And after arriving in Japan I made sure to run the lines in my head while on the way to visit temples or when queueing at the neighbourhood bakery for a couple of cream puffs.

This first day of October – when I’m due to perform the piece – is also the first day of term, ‘Commencement Day’, and as there are many other things going on at the University, my performance will take place at 5 pm – and not in a theatre or lecture hall but in a spare classroom. Not a problem. Tables are removed, chairs are arranged in semi-circles, I put on my dog-collar, then practise the moment in the play when the atomic bomb explodes, causing me to roll off a bench onto the floor, my shoes and clothes spinning into the air, as I manipulate (like a puppeteer) a small suitcase that flies in slow motion from one side of the room to the other. I then run through some cues with Maria, who has kindly offered to operate sound, while Riko has the day off to sight-see with her mother. At 4.45 pm, about thirty or more students and staff arrive to take their seats.

For some of them it’s their first day at the University, and it’s a bit of a shock for them to be told they will be attending a very unusual kind of seminar – a theatre performance at close quarters about a priest who survived the atomic bombing of Hiroshima.

We are now just awaiting our guest of honour – and here she is, Koko Kondo, atomic-bomb survivor, who having seen The Mistake last night, is now sitting in the front row of this University classroom, a few feet away from where I enact yet more events from that apocalyptic day in August, eighty years ago.

Thankfully, I don’t forget the words, I remember all the moves; the small suitcase, guided by my right hand, flies miraculously through the air, and the tale of Father Wilhelm, German Jesuit priest, unfolds.

After the performance and before our Q and A session, at which Koko will share her own experiences, two students approach me to thank me, saying they had never been that close to an actor performing before today. ‘We were right there with you in every situation, every moment of the priest’s story. There were times when we could barely breathe,’ they tell me.

I am reminded again of the power and effectiveness of simple storytelling – performed with conviction and nothing more than a few objects; where the audience fully engage their own imaginations, helping create the world of the play alongside the performer.

Koko Kondo was just ten months old when she survived the atomic bombing. She recounts how as a child, when she began to learn the facts about what had happened on that August day in 1945, she began to harbour a deep desire to find the men who had dropped that bomb and PUNCH them! Her father, Reverend Tanimoto, had been travelling to the United States, undertaking speaking tours of colleges and churches, to raise money to rebuild his church and later to help fund plastic surgery for some of the young women (the ‘Hiroshima Maidens’) who had been severely disfigured as a result of the blast.

In 1955, on yet another of these fund-raising tours, Reverend Tanimoto was surprised to find himself being ushered into a TV studio where he would be that week’s subject of ‘This Is Your Life’. (This episode of the programme can be found on YouTube – the account of the atomic bombing being interrupted for ‘a word from our sponsors’ – Hazel Bishop Nail Polish…) His family had been secretly brought out to the USA for the programme, Koko now being ten years old. When she saw that one of the guests on the show was Bob Lewis, the co-pilot of the plane that dropped the bomb, her anger instantly flared up. ‘I’m going to PUNCH him!’ she thought to herself. But when the co-pilot talked about his remorse (saying he had written in his logbook, immediately after the bombing, ‘My God, what have we done?’) and appeared to be tearful, Koko’s desire to punch him melted away. Instead she went over to him and quietly took his hand. Koko tells the students assembled here at the University today that this was a crucial turning point for her – setting her on the path of peace and forgiveness.

She then tells us how at one of her many subsequent talks, in schools and colleges around the world, relating this story of how her urge to PUNCH the co-pilot had melted away, one schoolboy made the comment, ‘When I raise my hand, I think of Koko.’

She couldn’t understand what the boy meant. You raise your hand when you want to ask a question. But it then became clear that this was a boy who was always getting into fights. What he meant was that now, when he raises his hand – in other words, to thump another boy – he will think of Koko and stop.

‘We can all make a difference,’ Koko encourages us. We can all stop and think before we let our fists fly, before we launch our drones, fire our missiles, threaten to use our nuclear weapons.

She shows me her old hardback copy of John Hersey’s HIROSHIMA, which features her father’s story but in which she is constantly referred to as his son. She tells me that when she met the author, the first thing she said to him was that he must correct this error – ‘I’m Tanimoto’s daughter, not his son!’ I wonder to myself if she’d felt like punching Hersey for this error…

A student, Patrick, asks Koko to talk more about ‘the journey of forgiveness’. He then reveals that he is from Rwanda – where, with its tragic recent history of genocide and savage tribal conflict, forgiveness is not a straightforward matter. Today, sitting with these peace studies students from all around the world, it becomes clear just how complicated the path to peace is.

At the end of the session, Koko thanks me for these two plays of mine that she has seen within the space of less than 24 hours. She encourages me to keep going. She herself is off to Rome shortly to speak at yet another conference, this time involving Catholics and Protestants. Koko is such a live-wire, feisty, funny, full of passion, it has been a real pleasure and inspiration meeting her.

Junko, Maria and I take a taxi back to the city and I allow myself another quiet evening of reflection.

Next morning, we are given a guided tour of the Peace Park and the Peace Memorial Museum. The museum is sombre and deeply moving; people walk through it respectfully, speaking with hushed voices.

There are black and white photos of the city before and then after the bombing; graphic images of victims and their injuries; a video display recreating the moment the bomb dropped and how it destroyed so much of the city.

In another room, objects that were recovered; children’s clothing; a child’s lunch box; a boy’s tricycle.

A number of Sadako’s exquisite tiny paper cranes are on display.

All I can think of is the waste, the loss, the futility. Pete Seeger’s lyrics come to mind… ‘When will we ever learn? When will we ever learn…’

Back out into the October sunshine, and it’s lunchtime. We are taken for a treat; ‘okonomiyaki’, Hiroshima-style. ‘Omelette’ doesn’t describe this wonderful dish, cooked on a hot plate right in front of us, by a woman who says she’s been doing this since she was eighteen, and will go on doing it until her dying day. The dish is scrumptious.

When we’ve eaten our fill, it’s time to say take our leave of Hiroshima City; we are collected in a minibus and driven to Takehara port to pick up the ferry to the island of Osaki Kamijima, in the Seto Inland Sea – and our final destination on this tour, the Hiroshima International Global Academy – where the next morning we will perform to the whole school, about 300 students and staff, in their cafeteria, which after breakfast will be swiftly transformed into an auditorium.

On the ferry, I feel my shoulders relax and a deep wave of contentment washes over me. Ahead of us and all around are countless islands; the scene is one of utter beauty; and when we reach our island we spend the first of our two remaining nights in the fabulous hotel we have booked. In a stunning location. Perched way above the sea. With its own ‘onsen’ (Japanese hot spring baths). And offering a superb banquet supper of the freshest fish you can imagine. The hotel is not expensive, it’s tremendous value for money – the only problem being it’s a heck of a long way from anywhere. But it’s the perfect place to complete our month in Japan.

Next morning at the school, we set up our props, and prepare to perform on the school’s raised stage at the far end of the cafeteria while three hundred students file in to take their seats – some of them a very long way from the stage. Two talented and helpful students have offered to operate the sound, under Maria’s supervision, and despite confessing to being very nervous, the two students carry it off brilliantly. Riko and I have to use every ounce of our vocal energy to compete with the noisy air-con and the clanking from the nearby kitchens preparing the students’ lunches, but all goes well.

Speeches of thanks are made, lunch is served, after which we have a long, leisurely discussion about the play and its themes with a dozen keen students. Everyone at the school has been so welcoming, so friendly; there’s a lovely vibe to the place; we learn that it’s a state school, but that the students board for months at a time. Soon it’s time to leave and we are waved off by the students we had been talking with and by members of staff, including the principal. They wave to us and we wave back for as long as we can see each other, as we are driven back to the hotel for our final night.

A huge party of elderly women has just arrived at the hotel – they’re from an agricultural group apparently and are enjoying a one night ‘reward’ break. Their laughter fills the building and fills the ladies onsen baths, next to the men’s onsen baths, where I float alone in the deliciously hot water gazing out at the sea as daylight begins to fade…

The ladies sound as if they’re having the time of their lives. Some of them looked very elderly indeed. But we too are having the time of our lives. Riko, Maria, Junko and myself sit down to another sumptuous fish feast (including a fresh seabass au gratin to die for), and then a final night’s sleep in Japan. This time tomorrow we will be on the plane home.

I wake in the morning and draw back the curtains to find rain and mist enveloping the islands. There is a melancholy beauty to the scene. I take an umbrella and head down to the beach for an hour or so, before we are due to depart.

It feels as if we are in paradise… this Inland Sea studded with countless green islands folding in and around each other, mysterious wreaths of mist lodging in their hills and mountains, the sea hypnotically calm. Someone said to me before we left for Japan, ‘If you stay on an island in the Inland Sea, you will never want to leave.’ They were right!

I walk further along the beach and find a path leading to a small shrine at the edge of the sea. It’s all so ineffably beautiful.

I feel sure we will come back to Japan again with The Mistake – there are so many places still to explore, so many places we want to perform the play in.

I approach the little shrine, ring its bell, drop in some coins, then bow my head, offering up heartfelt gratitude for the last 28 days. Unforgettable, exciting, deeply moving days, filled with so many new friends and connections.

Thank you…

Thank you…

Thank you…

THE END (for now…)